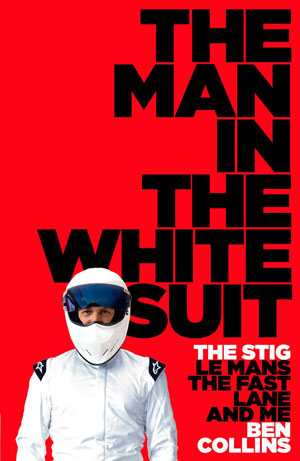

The Man in the White Suit The Man in the White Suit

The Stig, Le Mans, The Fast Lane and Me

On September 1st 2010, Ben Collins and his publishers

won a High Court case, overturning an injunction

placed on them by the BBC that prevented Ben

releasing his autobiography. That landmark decision

opened the way for HarperCollins to press the

button that set the presses rolling, and a fortnight

later, The Man in the White Suit hit

the bookshelves.

Within

its 300-odd pages Ben tells a remarkable story

and explores a myth. As many within the motorsport

industry had accepted for years, he confirms

that he, Ben Collins, is (or was!) The Stig.

That white-suited faceless one, the perplexing

and inscrutable test driver who, as everyone

knew, could punch a horse to the ground with

a single blow, never blinked, and had a left

nipple shaped like the Nürburgring, was

actually a chap from Bristol, married with three

children.

The

announcement swept across the media like the

1987 hurricane, toppling legend and folklore

like so many lofty poplars, and sending lanky,

curly-haired TG presenters (allegedly) apoplectic

with rage. It was all a bit bewildering at

the time, and some wondered what the fuss was

all about. After all, hadn’t the media

exposed Ben almost a year previously? Hadn’t

even the BBC’s

own publication, the Radio Times, run a feature

that pointed the finger at Ben? It was bizarre.

Now, a month later, the dust has settled, and

Ben’s chat show appearances are all but

over. In that atmosphere of relative calm we

can have a look at the item that created this

furore; Ben’s book.

The

Man in the White Suit is

the tale of a man only a very few people knew,

but everyone had heard of: Ben Collins, alias

The Stig, and it falls into two fairly distinct

halves. The first bobs and weaves like Cassius

Clay on PowerBoks, dancing some chronoclastic

tango as it swirls between Ben’s first Top

Gear “audition”,

his childhood in America, trials to join the

Army, and the realisation that a future in Formula

1 was probably beyond his grasp. The second half

concentrates on Ben’s experiences as Top

Gear’s Stig, from testing high-performance

supercars to firing up the Blackpool illuminations.

Ben’s early dream had been to become a

fighter pilot, but failing the 20-20 vision test

put paid to that. Ben could have made it as an

Olympic-standard swimmer, but you get the feeling

that the early morning plunge and tedious training

sessions didn’t really appeal. Instead,

Ben looked to motor racing, and with the help

of his Dad, he embarked on what proved to be

a very successful grass-roots introduction.

Ben

joined the ranks of those many hundreds of

talented, eminently capable and possibly mercurial

racing drivers who could have made it all the

way to Formula 1. In Ben’s case, he got

closer than most, and certainly made many of

the right moves, but like all those others, lost

out for the simple fact that he hadn’t

got the financial backing. Money, supposedly,

talks. In motor racing it positively screams,

and Ben’s tale of oh-so-nearly-but-not-quite

comes across strongly in the opening chapters.

If

what he says is accurate, then Ben’s

case was a very strong one, but he arrived too

late at the party. Most of those around him were

a year or two younger and had flourished in the

karting academy. They were mere whippets compared

to Ben’s Great Dane, and being too tall

to have made it in karts was a factor that worked

alongside his lack of money to deny him the future

he craved. Few, aside from Ben’s good friend

Mark Webber, have been tall, lanky, and successful

Formula 1 drivers.

Ben

changed direction, and looked for drives in

sports and GT cars. Luck smiled, and chance

encounters with the likes of Werner Lupberger

created the introductions and opportunities that

lead to a Le Mans debut with Ascari. I remember

Le Mans in 2001, and recall being eternally grateful

that my work that year allowed me to stay indoors

for much of the race. There I could watch the

timing screens and follow the race on TV, while

drivers like Ben – and particularly those,

like Ben, in open-topped prototypes – endured

hour after hour of unrelenting rain.

It

was a Biblical deluge that took no prisoners.

Track conditions were treacherous and totally

unforgiving, but Ben relished every moment, and

for four hours was consistently the quickest

driver on the track, sometimes by as much as

ten seconds a lap. It was the kind of performance

that makes stars, opens the eyes of factory head-hunters,

and secures a top flight future. In Ben’s

case, it didn’t, and for two very simple

reasons. It

was a Biblical deluge that took no prisoners.

Track conditions were treacherous and totally

unforgiving, but Ben relished every moment, and

for four hours was consistently the quickest

driver on the track, sometimes by as much as

ten seconds a lap. It was the kind of performance

that makes stars, opens the eyes of factory head-hunters,

and secures a top flight future. In Ben’s

case, it didn’t, and for two very simple

reasons.

Firstly,

the car didn’t take the lead,

as it evidently would have done. In fact, it

didn’t even record a worthy top-five finish,

because soon after Ben had unlapped himself,

and was chasing down on the leading Audi, a simple

five-bob bit of wiring gave way. He coasted to

a halt at Indianapolis and the Ascari was out

of the race. Even so, his stint had been so extraordinarily

brave, so stunningly quick, that surely someone

would have noticed? Well, no, and for Reason

Number Two. All this happened in the middle of

a miserably wet night, when chief executives

and decision makers were tucked up in bed, leaving

the hard work to pitwall managers and engineers.

It must have been a bit like the star performer

in a stage production coming out for the curtain

call only to discover that the audience has abandoned

the theatre because of a burst pipe. It’s

a sad fact in endurance racing that remarkable

stints from mid-race drivers are so often forgotten,

simply because it’s the results sheet that

records those races for posterity. If the car

fails, so does the memory.

Ben

and the Ascari did win races, and the nimble

A410 could have become a very successful sports

prototype if the reliability had been better.

2002, the year after Ben’s Le Mans debut

with the works team, the car finished 6th at

Sebring (although Ben recalls it as fifth!) and

was running high at Le Mans too before a suspension

failure pitched the car off-piste. That effectively

signalled the end of the Ascari LMP works effort,

and with other opportunities drying up, Ben was

forced to consider a back-up career; the Army.

After

failing to pass physical for the Air Force,

having to join the pongos must have seemed like

second-best for Ben, but he nearly didn’t

make it through the Army medical either. This

time it was because his hearing had suffered

from nearly ten years with his head stuffed up

against a racing engine, and he needed a surreptitious

in-ear deaf-aid to sneak through the examination.

He joined the Army Reserve Regiment and embarked

on a gruelling sequence of training exercises

that weeded out the top twenty or so from over

200 new recruits. Ben made the grade.

As

luck would have it, 2003 was the year it all

kicked off again for Ben. His appointment as

the new Top Gear Stig, replacing Perry McCarthy’s “Black

Stig”, was confirmed. Ironically, Perry

had lost the job because he’d admitted

to his alter ego in an autobiography.

His “death” was staged to great effect

when the Jag he was supposedly driving was catapulted

off the flight deck of an aircraft carrier and

sank without trace.

Perry

had lasted little over a year, and long before

his admission appeared in print, his identity

as the Stig was common knowledge. Ben’s

characteristic dedication to duty ensured he’d

hold onto the job for more than seven years,

and even if his erstwhile colleagues are reluctant

to admit it now, Ben was largely responsible

for establishing the style and persona that came

to epitomise his enigmatic Top Gear character.

Like many good actors, Ben took the part and

built it up, creating a role for himself that

made him increasingly indispensable.

Ben

pitched in as the “White Stig” with

gusto, and ultimately did much to establish what

became the mysterious cult of The Stig. Back

in 2003, when he embarked on his journey as the

fourth TG presenter, the rest of his life was

also falling into place. His long-standing on-off

relationship with Georgie, who would later become

his wife, was flourishing once again; he had

a future in the Army; he had a paying job (albeit

a rather open-ended one) with the BBC; and he

was back in the driving seat with a winning race

team; RML. Ben

pitched in as the “White Stig” with

gusto, and ultimately did much to establish what

became the mysterious cult of The Stig. Back

in 2003, when he embarked on his journey as the

fourth TG presenter, the rest of his life was

also falling into place. His long-standing on-off

relationship with Georgie, who would later become

his wife, was flourishing once again; he had

a future in the Army; he had a paying job (albeit

a rather open-ended one) with the BBC; and he

was back in the driving seat with a winning race

team; RML.

The

American craze for racing round in circles

had arrived in little ol’ England in the

shape of the astonishing Rockingham Oval. This

massive colosseum of a racetrack had recently

been built on wasteland outside Corby in Northamptonshire,

just down the road from RML’s Wellingborough

headquarters. They were to run one of the stock-built

cars that would mimic the Stateside NASCAR championship,

called ASCAR (Ass-car!? queried the

incredulous Yanks) in Europe, and sponsored by

the Army. Ben’s newfound status with the

ARR made him the perfect candidate for the driver’s

seat. An initial trial proved he was well up

to the task, leading both races and winning one.

Despite a lack of funding, RML persevered with

the season, and Ben duly rewarded their faith

by dominating the year and taking the title.

If

Ben believed this put him back on track, in

every sense, for a career as a racing driver,

he soon had to think again. RML withdrew, and

his replacement car for 2004 with another squad

was a total dog. Things went from bad to worse,

and before 12 months was out, Ben’s racing

future was back to square one.

Ben’s loss is his reader’s

gain, because from this point onwards the book

regains a cohesive structure that had been

in danger of slipping out of reach during the

mid-race stint. Trying to juggle tales of derring-do

in the Brecon Beacons with his early days at

Dunsfold, while simultaneously keeping us up

to speed on his racing exploits and (admittedly

only in passing reference) his personal life,

seems to have been a bit of a challenge, but

having weathered the storm, Ben then settles

down into a more regular pattern focused upon Top Gear and The

Stig.

That’s not to say that I didn’t

enjoy the opening sequences – I did, and

thoroughly so, probably helped by the fact that

Ben was recalling incidents in his life in which

I had played a very small part. His accounts

of racing at Le Mans are vibrant, pacey and well-crafted.

His descriptions of overcoming the challenges

of forced marches through the mountains of Wales

are gritty, dark and atmospheric, capturing the

physical pain in equal measure with the elation

of success. It’s a good read, but it’s

the second half of the book that will be this

book’s major appeal, at least to the Top

Gear cognoscenti who, one hopes for Ben’s

sake, will propel The Man in the White Suit into

the best-seller chart.

Here

Ben devotes the pages to his life as The Stig,

and they’re packed with anecdotes

about celebrities and stunts, exotic cars, glamorous

locations and his relationship with the guys

on Top Gear. As anyone who’s met him will

affirm, Ben’s an affable guy; friendly,

open, and easy-going, and he obviously slipped

into the groove very readily. He soon learned

what was required of The Stig, understanding

the film crew’s expectations yet ever conscious

of their skill and the risks they took. He also

came to know his fellow presenters, developing

a respect for all three of them: Jeremy Clarkson

for his abilities as a quick-fire presenter and,

it seems, a bewitchingly competent driver; Richard “Space

Hopper” Hammond for his selfless bravery

and sense of fun; and James May for his encyclopaedic

knowledge and baffling capacity to portray a

slightly off-planet personality which, if not

exactly true to life, was the perfect foil to

his colleagues. Here

Ben devotes the pages to his life as The Stig,

and they’re packed with anecdotes

about celebrities and stunts, exotic cars, glamorous

locations and his relationship with the guys

on Top Gear. As anyone who’s met him will

affirm, Ben’s an affable guy; friendly,

open, and easy-going, and he obviously slipped

into the groove very readily. He soon learned

what was required of The Stig, understanding

the film crew’s expectations yet ever conscious

of their skill and the risks they took. He also

came to know his fellow presenters, developing

a respect for all three of them: Jeremy Clarkson

for his abilities as a quick-fire presenter and,

it seems, a bewitchingly competent driver; Richard “Space

Hopper” Hammond for his selfless bravery

and sense of fun; and James May for his encyclopaedic

knowledge and baffling capacity to portray a

slightly off-planet personality which, if not

exactly true to life, was the perfect foil to

his colleagues.

Although The Stig played a boundless variety

of roles within the Top Gear panoply,

it was his coaching of the Stars in the “reasonably

priced car” that occupied most of his time

at Dunsfold. As a result the index in the book

reads like a who’s who of contemporary

celebrity, and Ben recollects their strengths

and weaknesses, foibles and idiosyncrasies in

an amusing and insightful way. Sportsmen and

women such as Usain Bolt, Lawrence Dallaglio

and Ellen MacArthur rub pages with comedians

like Harry Enfield, Eddie Izzard and Jimmy Carr.

Musicians Lionel Ritchie and Jay from Jamiroquai

are analysed and reported with as much enthusiasm

and honesty as filmstars Ewan McGregor, Tom Cruise

or Hugh Grant. There’s also room for the

ladies, of course, with Cameron Diaz, Geri Halliwell,

Sienna Miller, Jodie Kidd and Katie Price all

being strapped, some more tightly than others,

into the driving seat. Although The Stig played a boundless variety

of roles within the Top Gear panoply,

it was his coaching of the Stars in the “reasonably

priced car” that occupied most of his time

at Dunsfold. As a result the index in the book

reads like a who’s who of contemporary

celebrity, and Ben recollects their strengths

and weaknesses, foibles and idiosyncrasies in

an amusing and insightful way. Sportsmen and

women such as Usain Bolt, Lawrence Dallaglio

and Ellen MacArthur rub pages with comedians

like Harry Enfield, Eddie Izzard and Jimmy Carr.

Musicians Lionel Ritchie and Jay from Jamiroquai

are analysed and reported with as much enthusiasm

and honesty as filmstars Ewan McGregor, Tom Cruise

or Hugh Grant. There’s also room for the

ladies, of course, with Cameron Diaz, Geri Halliwell,

Sienna Miller, Jodie Kidd and Katie Price all

being strapped, some more tightly than others,

into the driving seat.

Ben

evidently has admiration for many of those

he tutored into the delights of Gambon or the

Hammerhead, and especially celebrity chefs Jamie

Oliver and Gordon Ramsay. Both passed muster

with flying colours, as did Mr Nasty himself,

Simon Cowell. Even comic turned actor Johnny

Vegas, who’d never really driven before,

clocked an almost passable time under Ben’s

direction, but like all the others, had no idea

who’d transformed his hesitant hops into

fluid motion. Ben was always hidden behind the

darkened visor, and if ever he met one of his

protégés again under different

circumstances, had to feign ignorance and walk

on by.

Ben fills in the gaps on several of his Top

Gear highs and lows – the Bugatti

Veyron clearly left a lasting impression, as

did the awesome but aerodynamically challenged

Koenigsegg CCX. Ben’s heartfelt concerns

over Richard Hammond’s crash in the Vampire

jet car are expressed with compassion and a

genuine sense of anxiety (if rather briefly),

and he rounds off with some zesty recollections

of some of Top Gear’s best-remembered

stunts, including blowing up a Mitsubishi Evo

7 with his old chums in the Army. Ben fills in the gaps on several of his Top

Gear highs and lows – the Bugatti

Veyron clearly left a lasting impression, as

did the awesome but aerodynamically challenged

Koenigsegg CCX. Ben’s heartfelt concerns

over Richard Hammond’s crash in the Vampire

jet car are expressed with compassion and a

genuine sense of anxiety (if rather briefly),

and he rounds off with some zesty recollections

of some of Top Gear’s best-remembered

stunts, including blowing up a Mitsubishi Evo

7 with his old chums in the Army.

The

end, when it comes, is the only disappointment

in an otherwise very enjoyable romp. I’m

sure there was so much more of this story to

tell, but Ben throws in the towel almost as an

afterthought. The reader is just getting into

the swing of another tale about the Veyron when,

in three short paragraphs, Ben’s career

as The Stig abruptly ends. Aside from a few hints

that things at Dunsfold weren’t going as

smoothly as they once had, there’s no warning,

and very little explanation, for what must have

been a monumental life-changing decision. Although

I can accept that Ben was under pressure to get

the book published soon after the High Court

decision was announced, I still believe this

final instalment could have been given more of

a flourish and tied off a little more neatly.

That

aside, Ben has a frenetic, edgy style that

keeps the book rattling along at a fair old

pace. I have to be honest and admit that this

is often not the Ben I’ve come to know. There are

phrases and a word structure here that I could

never hear coming from Ben in conversation, and

I suspect he’s made a huge effort to adapt

his style to meet the expectations of his Top

Gear fanbase. There’s a potential

350 million readers out there, dedicated TG enthusiasts

from across the world, who might be tempted to

buy his book, and those that do won’t be

disappointed. It’s a far better read than

most “celebrity” authors ever manage,

and it will largely meet the expectations of

those seeking an insight into the shadowy, furtive

world of The Stig. That

aside, Ben has a frenetic, edgy style that

keeps the book rattling along at a fair old

pace. I have to be honest and admit that this

is often not the Ben I’ve come to know. There are

phrases and a word structure here that I could

never hear coming from Ben in conversation, and

I suspect he’s made a huge effort to adapt

his style to meet the expectations of his Top

Gear fanbase. There’s a potential

350 million readers out there, dedicated TG enthusiasts

from across the world, who might be tempted to

buy his book, and those that do won’t be

disappointed. It’s a far better read than

most “celebrity” authors ever manage,

and it will largely meet the expectations of

those seeking an insight into the shadowy, furtive

world of The Stig.

That

said, I can’t help feeling a little

sad, and even some degree of personal loss, that

the enigma that has been The Stig is no more.

I rather enjoyed being one of those few who shared

the knowledge of The Stig’s true identity.

There was a certain frisson of quasi-celebrity

from knowing that others knew that I knew, but

knew I wouldn’t tell. I’m sure I’m

not the only one who’ll miss that. Ben

undoubtedly will, but as he insinuates in the

final chapters of the book, he was left with

little choice. The “White Stig” had

run his course. It had been a wonderful experience,

and enormous credit to Ben for keeping the mystery

alive for so long. Regrettably, however, the

unrealistically restrictive contract, the lack

of appreciation for the character he’d

created, (but could never benefit from) and the

enormous imbalance between his perceived status

within the Top Gear hierarchy and the meagre

paypacket he took home meant that the end was

in sight.

If

the writing wasn’t actually on the

wall yet, it certainly had to go down on paper,

and Ben needed to have everything in place before

the fan started spinning. He tells us there’s

an unfinished graffito on the wall in the Dunsfold

dunny that reads “Richard Hammond is a

. . .” One suspects that others far more

colourful and invective will have joined it by

now, and all signed “JC”. If

the writing wasn’t actually on the

wall yet, it certainly had to go down on paper,

and Ben needed to have everything in place before

the fan started spinning. He tells us there’s

an unfinished graffito on the wall in the Dunsfold

dunny that reads “Richard Hammond is a

. . .” One suspects that others far more

colourful and invective will have joined it by

now, and all signed “JC”.

Some say he can read a book from its cover,

and can control the keyboard merely by using

the power of his mind, but we now know him simply

as Ben Collins, author and one-time Stig.

Postscript

Ben has joined

Channel 5’s Fifth Gear programme

as a co-presenter with Tiff Needell, Vicki

Butler-Henderson and Jason Plato. He made his

first appearance tonight, Friday October 8th,

track-testing a dragster at Santa Pod raceway.

Channel 5 head of factual entertainment, Steve

Gowans said that they were "delighted

to have Collins on board. It will be great

to see him going head-to-head with Jason and

Tiff, the best drivers on television." Check

out the Fifth

Gear website for more details.

Ben

has recently launched a new website: Ben Collins

For

further information, please contact the publishers, HarperCollins.

|